The Monday before Thanksgiving, I awoke to my personal nightmare: I had been reported for abuse on Twitter (my favorite thing to look at while I crap), and my account was frozen.

I wasn’t totally shocked, but I was surprised the situation had gone this far. More importantly, the experience gave me unique insight into how Twitter’s moderation system actually works, from the inconsistent replies it gave to people who reported my tweets to its complete silence after I filled out an “appeal” to reinstate my account.

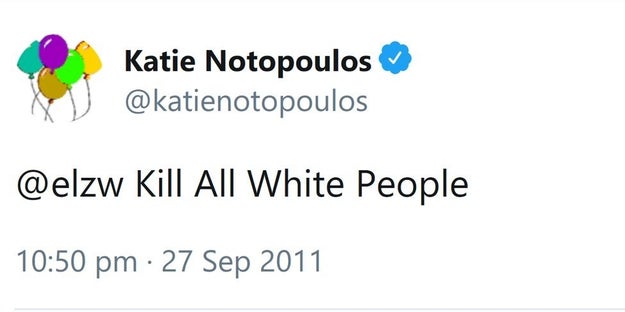

A few days before, I got a flood of replies to an old tweet from 2011 that said “kill all white people”.

I’m sure in 2011 I thought this was a funny joke (look carefully, and you will notice the Ironic Capitalization), though it’s not so funny now when there are Literal Nazis running amok. The ironic thing about Literal Nazis is that they have weaponized taking things literally. And that’s what they did here.

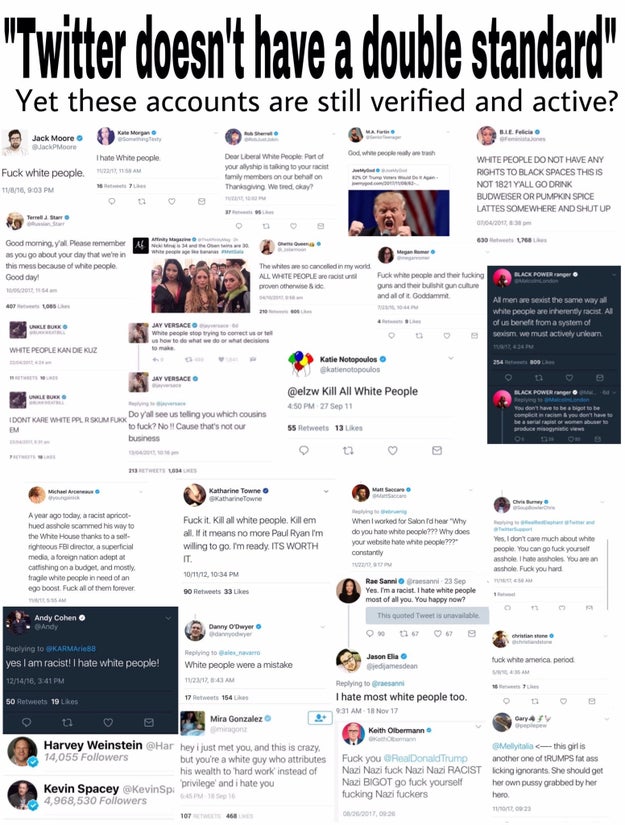

The day before my tweet was reported, Twitter had de-verified Richard Spencer and a few other high-profile white nationalist accounts. In response, their supporters wanted to expose Twitter’s supposed hypocrisy for allowing verified users to tweet mean things about white people.

A few larger white nationalist or alt-right Twitter accounts shared my tweet as well as some similar ones from verified users. My guess is someone just searched a few phrases like “I hate white people” and picked out the verified accounts. Someone even made this collage:

The replies feigned shock and fear at the outrageous nature of the tweet and plenty suggested it should be reported to Twitter.

“It’s OK to be white” is the latest meme and slogan of the alt right; it’s a deviously polite attack on social justice while narrowly skirting overt white supremacy. It’s not the 14 words, it’s just “OK”. The coordinated campaign to find people who had said anti-white tweets and then report them for abuse is part of this fixation on reverse racism being perpetrated by their fellow whites. It’s not surprising to me that some of the replies to me said that exact phrase.

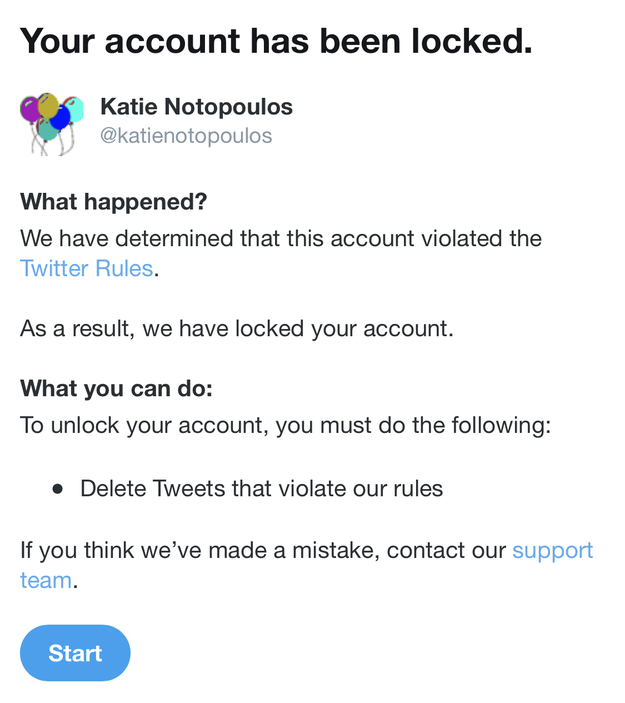

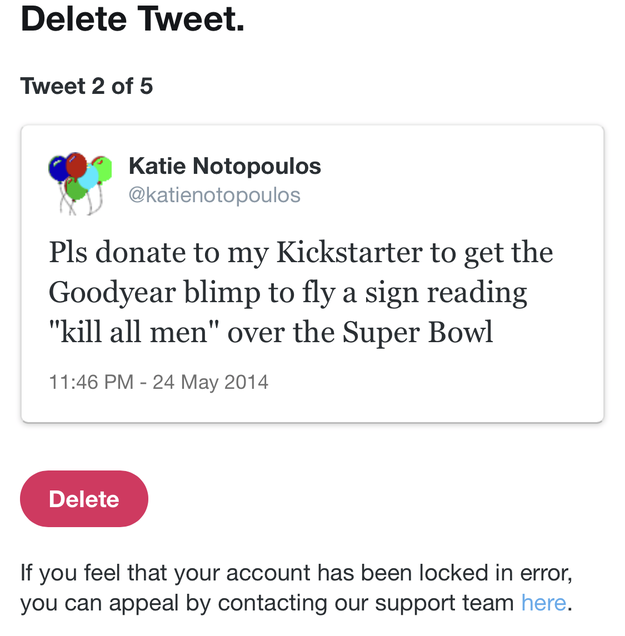

I ignored the angry replies; I assumed it would just die down and they'd move on. But then three days later, my account was locked – the flood of reports had worked. When I opened Twitter, I was prompted to delete 5 offending tweets. The first was "kill all men" – puzzling, since that wasn't even one of the tweets that the trolls had been replying to.

Twitter gives you an option to appeal if you think your account was locked in error. I believed this was clearly a mistake, so I filed my appeal.

And then I waited. 10 days.

During this time, I couldn’t look at Twitter. Locked, as opposed to suspended, is a purgatory where your account still exists and people can view it, but you can’t tweet, read your timeline, or access DMs. Weirdly there’s a small loophole because Tweetdeck is such a wonky product that my timeline kept updating, even though my replies didn’t.

It is not a secret that Twitter has a two-tiered system, where celebrities and verified users can get support in ways that the unwashed masses don’t. This isn’t because there’s some special second technical system for important accounts, just that the more access and influence you have, the greater your ability to talk to a Twitter employee — not just a contractor doing customer support — to get help. When Rose McGowan was briefly suspended, she was reinstated 12 hours later after getting in touch with her team; last weekend, a New York Times account was locked after a tweet about Justin Trudeau was flagged by a moderator as “hateful,” and the account was unfrozen 24 hours later. If this happened to a BuzzFeed official account, we would immediately reach out to Twitter for help. Celebrities and media can reach out for help don’t have to wait over a week for customer support. In cases like McGowan’s — she was in the middle of an important critique of harassment in Hollywood when she was suspended — this kind of prioritization is a good thing. But for so many who’re serially abused on the platform, it’s a source of endless frustration.

As a tech reporter for BuzzFeed News, I have some amount of access to Twitter. But I wanted to see how the process works for a normal person, not a tech reporter with a large media organization that also does business with Twitter.

So I waited. Thanksgiving passed. I actually talked to my family instead of hiding in the bathroom to look at Twitter. It wasn’t so bad! I read headlines in the Apple News app (and the BuzzFeed News app, of course). I remained blissfully unaware of the often toxic conversation that was surrounding the news. In a group text, someone mentioned something about “the NYT Nazi”. I thought he meant that someone discovered a Nazi was working at the Times.

As far as my offending tweets, I didn’t delete them and get my account back right away for two reasons:

The first is because I think there’s some merit to explaining why or why not one might consider my tweet a serious piece of hate speech. I can think of nothing more tiresome than debating whether “kill all white people” is the same as “kill all black people”, so I’ll spare you. Was I joking? Of course. But being 100% serious isn’t really a requirement for harassment. If someone tweets “I’m going to come to your house and kill you” at me, I don’t have to prove they truly mean it, and I shouldn’t have to. Perhaps one of the weird elements of this is that what seemed like funny satire embedded as part of a longer (now deleted) chain of replies in 2011 doesn’t work at all in 2017. I would have never tweeted that now; even the 2013 “kill all men” tweet is incredibly dated in its ironic misandry. A relic of a different part of ‘Weird Twitter.’

The second way of looking at this it is much more relevant: Viewed in the context of Twitter culture in 2017, it is very obviously a bad faith campaign by white nationalists and alt-right accounts to target members of the mainstream media for harassment by exploiting Twitter’s policies, which are riddled with loopholes and vague interpretations.

In fact, Twitter’s abuse policy is so flaky that the platform couldn’t seem to decide if my tweets broke the rules or not. A few weeks ago, someone filed a report about the very tweet my account was locked over and tweeted out screenshots showing the “kill all white people” tweet wasn’t a violation of Twitter’s rules.

The inconsistencies dredged up a few questions about moderation — namely, in the precious few moments a Twitter Trust and Safety moderator had with my report, what exactly were they evaluating? Did they look only at the words in my tweet? Or they did they look at the whole picture, including: What were the types of accounts that were making the reports? Did they happen to have white nationalists symbols or terms in their icons or bios? What kind of account is @katienotopoulos? Without context, the tweet is potentially very offensive. But with context maybe it looks different. For example, what — besides a coordinated trolling effort — would be the explanation for a flood of reports on a reply tweet from 2013 that had four likes?

So when I filed my appeal to the support team, they had a second chance to look at the situation. I wanted to know: Would they only look at the content of my offending tweets, or would they look at the context? This isn’t about my regrettable tweet from 2011, it’s about a broad cultural war between far right accounts and the mainstream. But will a Twitter support team member see this? Are they just making verdicts on single tweets, or do they act as a proper community moderator, someone who knows and understands the culture of the platform?

The appeal form tells you it takes “several days” for the support team to handle your request. After ten days, I got an email from Twitter saying they rejected my appeal. The “locked” status would remain, and my only option was to delete the tweet.

I reached out to Twitter as a journalist to find out more about the process. A representative told me that the company doesn't give out information on the timing of their support process, so the 10-day wait could be totally normal, or potentially even faster than average.

Twitter was also unable explain why or if “kill all white people” was the tweet that caused my account to be locked, nor could the company explain the inconsistency when others reported the tweet and were told it wasn’t a violation.

Once I had received my verdict from Twitter support, I had no choice by to move forward and delete the tweets. With a heavy heart, I had to say goodbye to my beloved children (my tweets).

In my case, the entire locked-account saga was pretty low stakes compared to others who rely on their accounts as a means to be heard and who’ve been locked or suspended on a technicality. But in the context of the last week, my situation feels increasingly frustrating — reasonable evidence that Twitter’s abuse enforcement priorities may be skewed in the wrong direction.

When Trump retweeted violent anti-Muslim content from a Britain First account, Twitter told CNN one reason for allowing the videos to stay up — then Jack Dorsey tweeted that they left them up for a different reason.

I’m not mad that the system works slightly differently for the president than it does for me. He also gets to drive through red lights on his motorcade and I’m not bitching about that. But the way Twitter decides what stays and what goes seems to be pretty arbitrary.

Twitter has been trying to figure out how to deal with abuse and harassment for the better part of two years now, and it continues to be a real shitshow with no clear fix in sight. Maybe they should treat it like an old school messageboard where community managers act fast and loose with the banhammer, doling it out without question. Maybe!

But for now, Twitter is getting played. They’re trying to crack down on the worst of Twitter by applying the rules to everyone, seemingly without much context. But by doing that, they’re allowing those in bad faith to use Twitter’s reporting system and tools against those operating in good faith. Twitter’s current system relies on a level playing field. But as anyone who understands the internet knows all too well, the trolls are always one step ahead.

from BuzzFeed - Tech https://www.buzzfeed.com/katienotopoulos/how-trolls-locked-my-twitter-account-for-10-days-and-welp?utm_term=4ldqpia

No comments:

Post a Comment