Stillfx / Getty Images

Ads for clothes, concerts, and flights to exotic destinations litter Facebook and Twitter. Soon, though, you may see a lot more ads for something more serious — prescription pills.

That is, if drug makers can avoid antagonizing the FDA.

From now until early January, the drug-regulating agency is collecting public feedback on how tweets promoting therapies should disclose their side effects, one step in the agency’s long-running attempt to regulate advertising on social media. The move follows Facebook beginning discussions with the FDA about ramping up efforts to populate the News Feed with drug ads.

Social media could help Big Pharma pinpoint more customers than traditional advertising. At the same time, the highly regulated drug industry faces unique challenges in trying to get their messages out in tweets and Facebook posts.

Pharmaceutical firms, which spent $6 billion on ads in 2015, are drawn to platforms like Twitter and Facebook for the same reasons as everyone else with something to sell: their data allows businesses to reach highly specific audiences. Think, for example, of Viagra ads aimed only at men over 50.

“To be able to target to very precisely who’s going to see those ads means that the industry would waste a lot less money, I suppose, and be able to see a better return on investment,” John Mack, who publishes the newsletter Pharma Marketing News, told BuzzFeed News.

Facebook and Twitter aren’t the only online networks that pharmaceutical companies are eyeing. Ad agency AbelsonTaylor recently praised Pinterest’s potential to reach patients, noting that, for example, its users are mostly women, and women make most health care decisions in their households. At least eight major pharma firms have Pinterest accounts, by Mack’s tally.

Still, traditional ads remain appealing because they have time-honored — and regulator-approved — ways to disclose drugs’ risks. Voiceovers on TV commercials breathlessly read side effects, and magazine ads print them in small fonts. But Facebook posts and tweets have much less room, and can be hard to distinguish from personal endorsements.

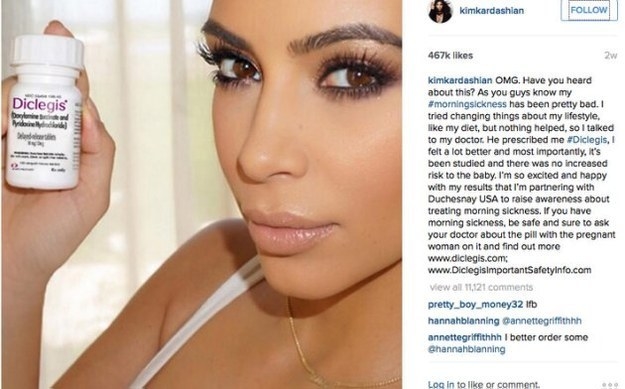

Kim Kardashian's now-deleted Instagram to promote a morning sickness drug, without the required safety information.

Their casual nature can breed bizarre situations like the FDA coming down on a Kim Kardashian selfie. In August, she Instagrammed a picture of herself with Duchesnay’s morning-sickness drug, which she was paid to promote, without mentioning its potential side effects, although she did link to a site with that information.

Kardashian deleted the photo after the FDA sent a warning letter to Duchesnay, and then reposted it with the side effects, from drowsiness to allergies.

“From a regulatory perspective, it’s a lot of pressure to think about fitting all that information into a four-inch mobile screen,” Danielle Salowski, industry manager for Facebook’s health team, told BuzzFeed News.

The social network has been beefing up that team, which has been around for about a year and a half, in an effort to bring in more pharmaceutical dollars. Salowski, who joined Facebook in May after working in ad sales at Twitter, said her team is a mix of pharma experts, digital industry veterans, and longtime employees.

They’ve been trying out creative ad formats. This fall, Bayer bought its first Facebook ad for a multiple sclerosis drug, which presented safety information in an auto-scrolling line of text, rather than a long paragraph. The scrolling feature had appeared in other Facebook ads, but not previously for pharmaceutical ads, according to Facebook. “Bayer chose Facebook because the multiple sclerosis community is actively involved in Facebook,” Bayer spokesperson Rose Talarico told BuzzFeed News by email. “We recognized an opportunity to reach them where they already were with information that was potentially relevant to them.”

Facebook keeps the FDA updated on the types of ads that pharmaceutical companies can buy, according to a Facebook spokesperson. But clients, not Facebook employees, are in charge of ensuring that their ads obey regulations, Salowski said.

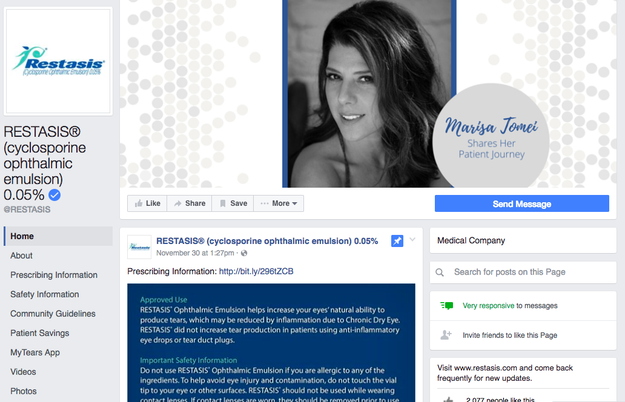

Beyond Bayer, some companies promote their products on Facebook pages — some obviously branded, others less so. Allergan does this for dry-eye disease medication and birth control, and AstraZeneca has a page for cholesterol-lowering drugs.

Allergan's sponsored Facebook page for its dry-eye disease drug.

One unique feature of Facebook — and social media at large — is the ability to leave comments. Commenting can help people feel more attached to a brand and bring their friends into the conversation. But, as Mack pointed out, horror stories about bad side effects or endorsements of drugs for unapproved conditions could be nightmares for pharmaceutical companies. Salowski said that Facebook lets brands turn off comments on posts and pages.

Liking a brand's Facebook page also potentially increases the chances that your friends will see it or related ads in their feeds. That feature could lead to inadvertent privacy violations if, say, you don’t want people to know you’re "liking" antidepressants. At the same time, Facebook allows people to adjust their settings so that friends won’t see ads based on their page likes.

Tweets, which are even shorter than Facebook posts, pose their own challenges. Last month, the FDA said it intends to study if it’s appropriate for a promotional tweet for a prescription drug to include a link to side effect information. It’s the latest chapter in the agency’s slow adjustment to advertising in a 140-character world. In 2014, it put out draft guidance for how pharmaceutical companies could use social media, but didn’t explicitly address whether links to information about risks were allowed.

Viral, targeted ads aren’t inherently dangerous, said Ameet Sarpatwari, an instructor at Harvard Medical School who studies pharmaceutical marketing. But he’d like to see social media companies make clear the potential dangers of medical products.

For example, he suggested, Twitter could label drug advertisements as such, instead of just “Promoted Tweets.” He also endorses links to side effect information, accompanied by language that underlines their importance, like “read about the risks here” (rather than a neutral phrase like “click here to learn more”). And he wants the platforms to allow researchers to study whether these steps are effective.

Sarapatwari’s concerns about social media ads reflect broader concerns about direct-to-consumer drug ads, which are only allowed in the United States and New Zealand. They can be incorrect or one-sided, so “what you get is a continual influx of information about how these products are going to be better and you should take them,” he said.

And on social media, he said, hype can go viral.

“We want to facilitate the flow of information,” he said. “But we don’t want to also allow something that is true, but misleading, to be able to influence decision-making on something of such a magnitude that it can impact health.”

LINK: Big Pharma Is Sponsoring A Flu Map On The Weather Channel

LINK: What Our Tweets And Google Searches Say About Our Health

from BuzzFeed - Tech https://www.buzzfeed.com/stephaniemlee/pharma-social-media?utm_term=4ldqpia

No comments:

Post a Comment