For Cassandra Smolcic, the trouble began at her dream internship. Handpicked to spend a summer working on movies at Pixar, the 26-year-old logged marathon hours, and more than a few all-nighters, at her computer and tablet. At first, she managed to ignore the mysterious pinching sensations in her hands and forearms. But by the time her internship ended and a full-time job offer rolled in, she could barely move her fingers.

For Skylar, a 12-year-old in South Florida who loves her laptop, phone, and tablet, the breaking point came at the start of sixth grade last fall. Suddenly her neck, shoulders, and back felt strained whenever she rolled her head, as if invisible hands were yanking muscles apart from the inside. All her neck-rolling, she worried, made her look like she was trying to cheat off someone’s test.

To be a perpetually plugged-in, emailing, texting, sexting, swiping, Snapchatting, selfie-taking human being in 2016, a little thumb twinge is the price of admission. There are the media-anointed outliers: the Candy Crusher with a ruptured thumb tendon, the woman who over-texted her way to “WhatsAppitis.” And then there are people like the 18-year-old woman who said, “If I’m scrolling down Tumblr for more than half an hour, my fingers will get sore.” “When I hold my phone,” a 22-year-old complained, cradling her iPhone in her palm, “my bottom finger really hurts.” A 30-year-old software engineer said his fingers “naturally curl inwards,” claw-like: “I remember my hand did not quite use to be like that.” Amy Luo, 27, suspects her iPhone 6s is partly to blame for the numbness in her right thumb and wrist. Compared with her old iPhone, she said, “you have to stretch a lot more, and it’s heavier.” Dr. Patrick Lang, a San Francisco hand surgeon, sees more and more twenty- and thirtysomething tech employees with inexplicable debilitating pain in their upper limbs. “I consider it like an epidemic,” he said, “particularly in this city.”

“I consider it like an epidemic, particularly in San Francisco.”

To be clear, no one knows just how bad this “epidemic” is. At best, we learn to endure our stiff necks and throbbing thumbs. At worst, a generation of people damage their bodies without realizing it. In all likelihood, we are somewhere in the middle, between perturbance and public health crisis, but for the time being we simply don’t — can’t — know what all these machines will do to our bodies in the long term, especially in the absence of definitive research. What we do know is that now more people are using multiple electronics — cell phones, smartphones, tablets, laptops, desktops — for more hours a day, starting at ever earlier ages. But we weren’t built for them.

Source for computer injury prevention tips: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons / Via orthoinfo.aaos.org

Growing up in the Rust Belt city of Greensburg, Pennsylvania, Smolcic was the kid who was always sketching characters from movies and cartoons. And in her adolescent years in the ’90s, computers became an important tool for honing her artistic talents: She made clip-art greeting cards and banners, and high school newspaper layouts, on desktop computers. At Susquehanna University, she went all in on graphic design as a career after she took a computer arts course on a whim. That meant long hours on various iMacs, and even more screen time when she went on to earn a master’s in graphic design at the Savannah College of Art and Design. Over the years, she’s also carried a flip phone, a Motorola Razr, a Dell laptop, and, at the moment, a MacBook Pro and an iPhone 6s.

Smolcic in Hong Kong

Courtesy Cassandra Smolcic

Machines were crucial to Smolcic’s burgeoning artistic career, as they are to so many of our lives. But it’d be hard to call them human-friendly.

Consider the minimum biomechanics needed to work a smartphone. Put aside all the other risks — of getting depressed and lonely; of sacrificing sleep, hearing, eyesight, and focus; of dying while snapping selfies on cliffs, or texting while walking or driving. The act of just using the thing is precarious.

Our heads sit atop our necks and line up with our shoulders and arms, just as a two-footed species’ should. But a forward-leaning head shakes up this graceful arrangement: The upper body drifts back, the hips tilt forward, and pretty much everything else — the spine, the nerves below the neck, the upper limb muscles — tightens up. Slouching is all too easy when we hold a phone in our outstretched hand or reach for a mouse. When we type on our laptops cross-legged or sprawled on our stomachs, our necks and shoulders strain from leaning into the low screens. (Yes, as counterintuitive as it sounds, you probably shouldn’t put a laptop on your lap.)

Our hands are uniquely capable of grasping objects, a useful trait for our branch–swinging primate ancestors. Especially remarkable are our opposable thumbs, free to flex, extend, curl, and press in all sorts of directions. But their inherently unstable joints didn’t evolve to be constantly pushed beyond their range of motion. Yet they are when we flick through our phones or, worse, tablets.

Dr. Markison in his San Francisco office

Stephanie Lee / BuzzFeed News

To Dr. Robert Markison, it’s clear: Virtually none of Silicon Valley’s inventions, from the clunky Macintosh 128K of 1984 to the sleek iPhone 7, have been designed with respect for the human form. Markison is a San Francisco surgeon who depends on his hands to operate on other people’s hands. He so believes in technology’s potential to harm — and treats so many young startup workers who confirm that suspicion — that he almost exclusively uses voice recognition software. He also has his own line of smartphone styluses that double as pens, with colorful barrels made of manually mixed pigments, pressure-cast resin, and hand-dyed silk.

On a recent afternoon in his office, Markison asked me to make a fist around a grip strength measurement tool, with my thumb facing the ceiling. It felt powerful, easy. Then he had me turn my palm to the floor, the keyboarding stance of a white-collar worker, and do the same thing; my grip immediately lost a noticeable amount of strength. “There’s no reason to think a mouse is a good idea,” Markison said.

Of course, many people with office jobs probably suspect that already. During the ’80s and ’90s, when computers — then also known as “video display terminals” — invaded workplaces around the world, employees felt their arms and fingers go numb, and headlines warned of the harm these newfangled devices appeared to be inflicting. In the early ’90s, telephone operators, journalists, clerical workers, and employees from other fields filed hundreds of lawsuits against the manufacturers of equipment such as computer keyboards, which they blamed for severe arm, wrist, and hand injuries.

All that worry woke a generation up to the physical (and psychological) toll of automated, ultra-efficient work. Then came furniture and appliances to align technology with our bodies. Ergonomic mice are gripped vertically, and foot mice save clicks. Slanted and split keyboards let hands relax. Desks convert to a standing position or have adjustable split levels for monitors and keyboards. Some software transcribes speech, other software alerts your boss when you type too fast.

But these inventions have been largely for desktops. The dizzying rise of cell phones, tablets, and laptops, fueled by the rush to make screens ever more portable and ubiquitous, have all but left human-centered design principles in the dust.

Chances are good you’re reading this on your phone. In fact, chances are good your phone was the first thing you looked at this morning and the last thing you looked at last night. Wake up to a phone alarm. Scroll, bleary-eyed, through email, texts, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram. Field more news and email on your phone on public transit (or, er, in the car). Sit behind a computer of some kind at work or school. All day your buzzing phone demands to be held, whether you’re out to lunch or, admit it, on the toilet. Come reverse commute, you’re once again head down on your phone, or an e-reader, until you finally take a break at home — by watching Game of Thrones on your laptop or tablet. Bonus points if you play Words With Friends while you do it.

Mark Davis / BuzzFeed News. Sources: New York Spine Surgery & Rehabilitation Medicine, Mayo Clinic, American Society for Surgery of the Hand

Last year alone, an estimated 164 million laptops and 207 million tablets were sold worldwide. Sixty-three percent of the world’s population had a mobile subscription; by 2020, more than 2.5 billion new smartphone connections are predicted to come online. We are surrounded by gadgets. Luo’s hand may hurt from holding her iPhone, yet her lifestyle leaves her little choice but to swipe and soldier on. “I have considered being on the phone less,” said the Twitter product designer, “but it’s kind of hard because it’s how I keep in touch with my friends and everything.” Her doctor told her to “absolutely stop” laptop work. Luo admits she doesn’t listen.

Eighteen hours, from waking up at 7 a.m. to going to bed at 1 — that’s how long Owen Savir, 35, says he’s on his Nexus 6P every day. (He keeps busy as the president of Beepi, an online car marketplace.) Savir’s pinkie sometimes goes numb under his phone, and the cover cuts his skin so much it needs a Band-Aid.

How would he feel, I asked, if his phone got taken away?

He paused. “I would use my other phone.”

“I have considered being on the phone less, but it’s kind of hard because it’s how I keep in touch with my friends and everything.”

Scientists don’t definitively know how all this activity affects our bodies. While some studies link hand ailments to heavy computer and video game use, far fewer have examined new devices like smartphones. “The phones have only been out 10 to 15 years at best,” said Jack Dennerlein, who directs the Occupational Biomechanics and Ergonomics Laboratory at Harvard University. “We haven’t had the long-term exposures to start seeing some of the more chronic issues that come up later in life.”

No reliable measurement of technology-related ailments exists. The closest thing is an annual survey of workplace injuries by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, whose data suggests that cases of musculoskeletal disorders, including carpal tunnel syndrome, have dropped over the last two decades. But these figures are at best “a very crude measure” of problems, said Dr. Kurt Hegmann, who directs the University of Utah’s Rocky Mountain Center for Occupational and Environmental Health. As Dennerlein put it: “They’re better than nothing.”

Hegmann offers some theories for why the numbers are shrinking: High-risk jobs like manufacturing are decreasing. Panicked workers in the ’90s likely reported nonexistent ailments before the hysteria subsided. Some offices may have became more ergonomic. And there are other reasons the numbers are probably off: Non-work-related factors like obesity can contribute to carpal tunnel, and if you’re constantly sending work emails but also Instagramming for fun, it’s hard to blame your sore hand on work alone.

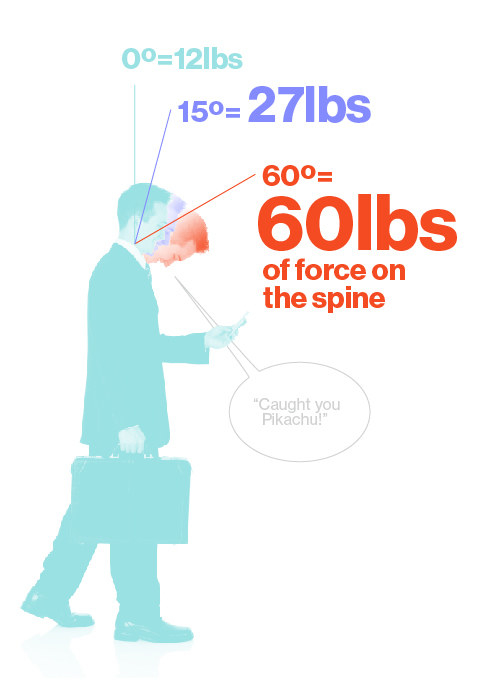

BuzzFeed News; Getty. Source: Surgical Technology International

However widespread phone-linked injuries may or may not be, a small cluster of studies suggests that they are real. A 2011 study of nearly 140 mobile device users linked internet time to right thumb pain, as well as overall screen time to right shoulder and neck discomfort. Another found that smartphone overuse enlarges the nerve involved in carpal tunnel, causes thumb pain, and hinders the hand’s ability to do things like pinch.

Upright, an adult’s head puts about a dozen pounds of force on the spine, according to a 2014 paper. But tilted 15 degrees, as if over a phone, the force surges to 27 pounds, and to 60 pounds at 60 degrees. (That’s the weight of four Thanksgiving turkeys.)

“It’s harmful when you’re younger, because the bones are still malleable and pliable and they may be disformed permanently,” said New York spinal surgeon Dr. Kenneth Hansraj, who wrote the paper after treating a patient “head down in his iPad, playing Angry Birds four hours a day.” Older people can suffer too, he said, because their spines are prone to narrowing, making them susceptible to injury.

But the doctor insists he’s no “cell phone basher.” “I love the ability to have a cup of coffee and contact 10 of my friends in 10 countries with one text and say, ‘I love this coffee,’” he said. “I’m just saying, my message is to keep your head up and be cognizant of where your head is in space.”

from BuzzFeed - Tech https://www.buzzfeed.com/stephaniemlee/whatsapp-doc?utm_term=4ldqpia

No comments:

Post a Comment